— Where the Past Guides the Present —

High in the cool mountains of Kintamani lies Bayung Gede, one of Bali’s oldest Bali Mula (also known as Bali Aga) villages—communities believed to preserve pre-Majapahit, pre-Hindu classical Balinese culture. The village forms a rare cultural enclave where rituals, architecture, and social structures follow ancient patterns that have long disappeared in other parts of the island. Walking through its narrow, north–south lanes, past bamboo-roofed houses and age-old mud-brick walls, visitors immediately sense a place where time moves differently, where traditions live on rather than fade into memory.

Where Bali Mula culture thrives

Bayung Gede is often regarded as the cultural ancestor of several later Bali Mula villages, including Penglipuran, and is recognized as the ritual center of the Gebok Satak cluster (banua). The most important collective gathering (usap gede) of this banua takes place biennially in Bayung Gede. Within this ritual hierarchy, the deities of the branch villages are conceptualized as the “children” of Bayung Gede’s senior deity, and it is their duty to visit their “parents” during major ceremonies, like purification rites (balik sumpah) held following the birth of opposite-sex twins or after major temple restorations. Participants in these gatherings commonly include delegations from Penglipuran, Sekardadi, Trunyan, Kedisan, and Pengotan. At the same time, Bayung Gede maintains reciprocal ritual obligations: the village sends representatives to Sukawana—specifically to Pura Puncak Penulisan—either for important ceremonies or to obtain holy water for roof-replacement rites at its Pura Bale Agung.

Unlike most Balinese villages, which orient their sacred spaces toward a holy mountain, the people of Bayung Gede consider the very center of the village to be the most sacred point. This inward focus is a key part of their unique worldview.

Most other Bali Aga/Bali Mula villages—such as Trunyan and Tenganan Pegringsingan—rely heavily on natural features like hills or lakes for physical protection. Rather than constructing the high, thick walls common in many other Balinese settlements, these communities historically prioritized geographic isolation. Bayung Gede brings this strategy to an even more pronounced level: the village is encircled by seven ravines, each densely overgrown with bamboo forests. These ravines form powerful natural barriers against tangible (sekala) dangers or potential intruders and are traditionally off-limits to alteration. Within them lie seven forest shrines (mertiwi), which are understood to safeguard the community from intangible, spiritual (niskala) threats. Only one main road approaches the village from the north, leading directly to its gate. This configuration of seclusion may have contributed to Bayung Gede’s ability to remain relatively autonomous in the face of the Gelgel Kingdom’s expansion and the far-reaching Majapahit influence that reshaped much of Bali in the 15th century.

Specific awig-awig (customary regulations) govern various aspects of social life in Bayung Gede. Newly married couples are prohibited from entering the family compound until they have paid the maskawin (bridewealth), which consists of two cows that must be handed over to the village authorities. In addition, the couple is required to undergo a period of fasting or tapa brata, during which they must reside in a small hut located on the outskirts of the village.

Residential rights within the village are reserved exclusively for the youngest child. According to local customary law, once the youngest son marries, the eldest sibling is obligated to leave the household. Rights to the family house are granted solely to the youngest child.

Funerary practices in Bayung Gede differ from those in other parts of Bali, particularly with regard to the gender of the deceased. Women are buried lying on their backs, a position symbolizing that women represent the earth and must therefore face the sky. Male bodies, by contrast, are buried facing downward, symbolizing that men represent the sky and must face the earth.

Entering a house

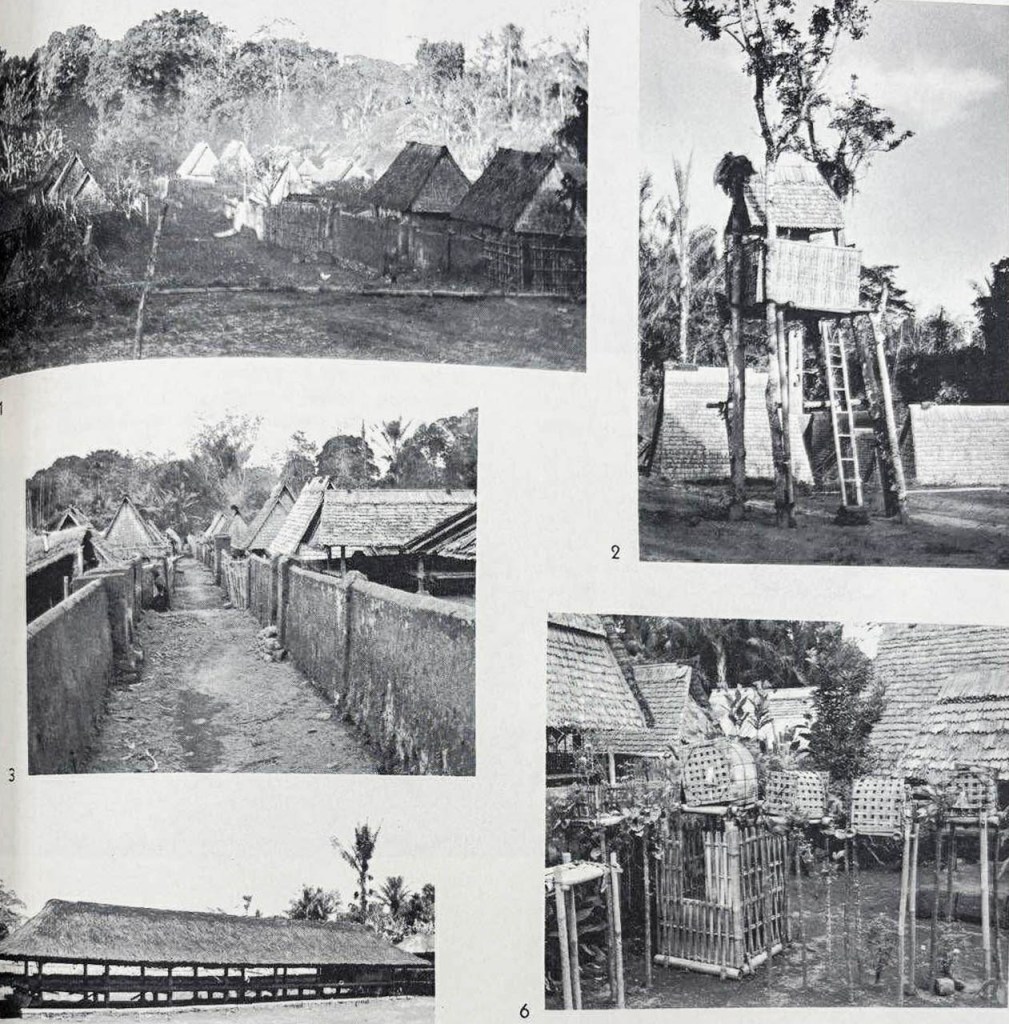

Bayung Gede’s houses reflect the lifeways of a traditional Balinese mountain community. As a Bali Aga village, its architecture preserves an older stratum of Balinese cultural and spatial organization. The settlement’s layout follows a linear, uphill–downhill axis, with houses arranged in orderly rows and their entrances facing a central corridor. The spatial order mirrors a tightly regulated social structure rooted in pre-Hindu Balinese principles.

Today, traditional roofs made from interwoven bamboo tiles, produced collectively through gotong royong (mutual cooperation), increasingly alternate with corrugated iron sheets. Yet villagers emphasize that proportion, orientation, and adherence to customary spatial rules matter more than the specific building materials, allowing the architectural tradition to remain recognizable and resilient despite gradual change.

Temples and ceremonies

Temples further strengthen the ancient identity. As mentioned earlier, Pure Bale Agung, the largest temple of the village, stands in the village center. The Pura Puseh in the village’s northeast preserves shrines in archaic forms—low, unfussed structures made from organic materials and stone. At the forest’s edge stands Pura Puseh Pinggit and Pura Mertiwi Dukuh, dedicated to the founding ancestor and central to major ceremonies such as Ngusaba Desa. In Bayung Gede, forests themselves are understood as sacred spaces—“living temples” where rituals are performed beneath the trees rather than in elaborate stone shrines.

The extraordinary Placenta Cemetery

One of the most remarkable traditions in Bayung Gede is the treatment of the ari-ari, the newborn’s placenta, considered in Bali as a child’s invisible sibling. Throughout Bali, placentas are washed, blessed, and buried beneath the family home. But Bayung Gede follows a different practice: the placenta is hung from the branches of trees at a designated sacred grove in the south of the village, known as the Setra Ari-Ari, the “placenta cemetery.”

The process is precise: the placenta is cleaned, placed inside a coconut shell, tied securely with a bamboo rope, and hung on a specific type of tree known as the bukak tree (Ficus superba). The bukak tree is seen as a living guardian that watches over the child. It is believed to possess a magical ability to protect the baby from illness, unseen disturbances, and black magic. The timing of the burial is also strictly regulated: it must occur in the morning or late afternoon and may not be performed during sunrise.

Dozens of coconut shells dangle from heavy branches, forming a mysterious and moving landscape of suspended lives. Villagers explain that the bukak tree’s sap has purifying qualities that neutralize the odor of decay.

By keeping placentas out of family courtyards, every home remains ritually pure, allowing priests and ritual specialists to enter without elaborate cleansing rites.

Birthplace of visual anthropology

Between 1936 and 1939, Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson conducted groundbreaking fieldwork in the mountain village of Bayung Gede. They documented social interactions, rituals, child-rearing practices, and emotional expression through an unprecedented combination of written notes, photography, and film. This innovative approach laid the foundation for what would later be called visual anthropology. Their over twenty thousand photographs and extensive film material revealed how children learned bodily techniques, how social norms shaped emotional life, and how ritual structured daily experience. These materials build the core of their book Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis (1942) and the influential film Trance and Dance in Bali (1952).

One of their most influential recordings is the sanghyang deling ritual, where two young girls in trance animate small puppets suspended between them, and sometimes become the puppets themselves, climbing on the shoulders of men and dancing with eyes closed. These scenes became foundational in the development of visual anthropology, shaping how culture is studied through images, movement, and behavior.

(Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis. New York Academy of Sciences, 1942.)

Despite its fame among anthropologists, Bayung Gede is still a peaceful community of roughly 2,000 residents. Its north–south streets remain quiet, dogs are rare, and old mud-brick walls stand as living testimony to centuries of maintenance. The philosophy of Tri Hita Karana, “Three Causes of Well-being”: harmony among humans, nature, and the divine, is enacted here in its most direct, landscape-based form. Although Bali Mula communities predate the full Hindu influence of the Majapahit period, they gradually incorporated Hindu cosmology into their rituals, village layout, and spiritual life to some extent, blending it with older animist and ancestral practices. In practice, Bali Mula villages follow principles of environmental balance, ancestral respect, and community cooperation, which align with Tri Hita Karana, even if their origins are older.

An ancient village living in the present

Bayung Gede is not a museum, but a vibrant and living community where rituals, agricultural cooperation, and ancestral traditions actively shape everyday life. It stands as a cultural stronghold within a sacred landscape, yet its people share the same hopes, challenges, and aspirations that connect us all.

Visitors are welcome to observe village life, but temples should only be entered with explicit invitation.

Bibliography

Adiputra, I Gusti Ngurah Tri. Jaga Baya Sekala lan Niskala As a Self Treaty Defence Basic Planning System of Balinese Mountain Traditional Settlment. Gap Gyan Journal of Social Sciences, 2/2, May 2019.

Bateson, Gregory, and Mead, Margaret Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis. New York Academy of Sciences, 1942.

Eisema, Fred Bali: Sekala and Niskala. Essays on Religion, Ritual, and Art. Singapore: Periplus Editions, 1996.

Kardinal et al. Pendampingan pemetaan bangunan tradisional di desa Bayung Gede Kintamani Bali. Buletin Udayana Mengabdi, 24(4), 276-281., July 2025

Lansing, J. Stephen. Perfect Order: Recognizing Complexity in Bali. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2006.

Suastika, I Nengah et al. Traditional Life of Bayung Gede Community and Its Development As Cultural Attraction. International Journal of Applied Sciences in Tourism and Events Vol.3 No.1, June 2019.

Sullivan, Gerald Margaret Mead, Gregory Bateson, and Highland Bali: Fieldwork Photographs of Bayung Gede, 1936-1939. University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Reuter, Thomas A. Custodians of the Sacred Mountains: The Ritual Domains of Highland Bali. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press, 2022.

Wijaya, Made Architecture of Bali. University of Hawai’i Press, 2002.

Connections to nearby temples

Bayung Gede has a close connection with the two concurring temples of the lake goddess Dewi Danu, Pura Ulun Danu Batur and Pura Hulundanu Batur in Songan. Its ties are strong to the villages of the Batur lake, which call themselves “the lake stars” (Wintang Danu). Bayung Gede’s long-standing connection to Pura Puncak Penulisan, mentioned earlier, further situates the village within a wider network of highland ritual alliances.

Previous temple:

Next temple:

Next region:

Photos and text © 2025 Alida Szabo, unless otherwise noted.