— Hidden and Unspectacular, but Ancient and Special—

Meaning of its name: Pancer ing Jagat means” the center of the universe”

Also called: PURA DA TONTA, PURA RATU SAKTI PANCERING JAGAT, PURA GEDE PANCERING JAGAT, PURA PANCER JAGAT. Da Tonta is the name of the ancient statue kept in the temple, also called Ratu Sakti or Ratu Gede.

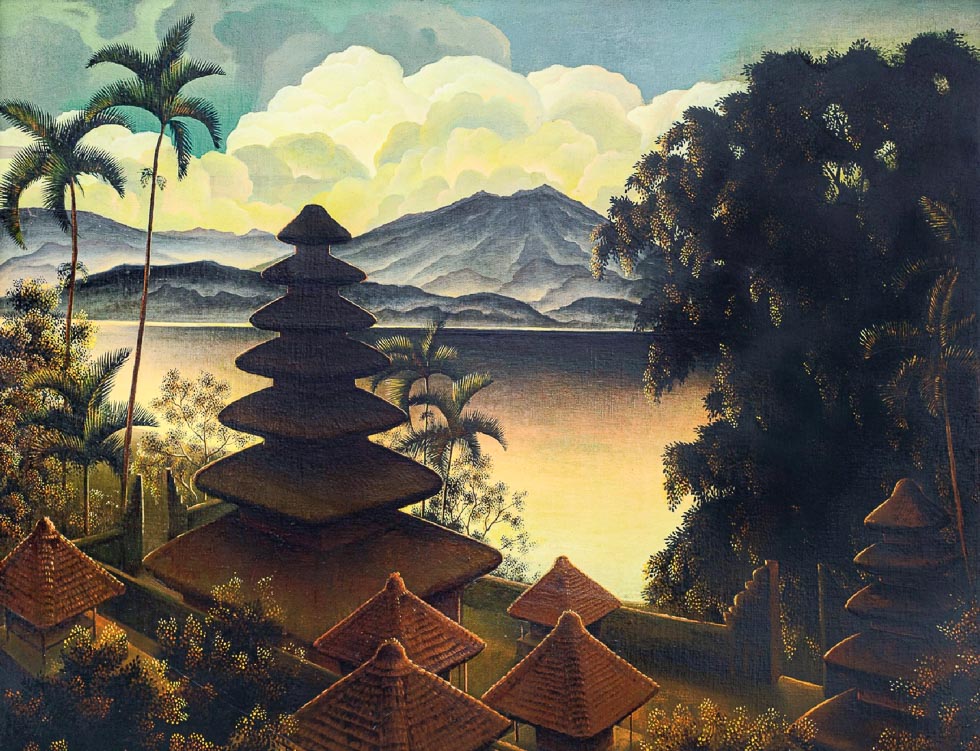

Location: At the eastern shore of Lake Batur

Map: Terunyan, Kintamani, Bangli, Bali, Indonesia

Dates back to: Megalithic era

Region: Mount Batur

Requirements for visit: The temple is not open for public. Special permits can be granted.

The remote village of Trunyan

On the eastern shore of the spectacular Lake Batur lies the village of Trunyan, long known as one of Bali’s most isolated and mysterious communities. For centuries, it could be reached only by boat; a narrow paved path to the village was built just about a decade ago. Trunyan is often described as the ultimate Bali Aga or “original Balinese” village, referring to those who have preserved pre-Hindu traditions that existed before Hindu-Javanese cultural influence. The villagers themselves, however, prefer the term Bali Mula, meaning “the true origin of Bali.” Archaeological finds—such as stone tools attributed to Pithecanthropus erectus—suggest that people have inhabited this area since prehistoric times.

A temple of megalithic origins

The temple of Trunyan preserves striking traces of pre-Hindu megalithic culture. Upright stones are enshrined within small sanctuaries, while others are draped in the traditional black-and-white poleng cloth, representing the balance between opposing cosmic forces. These elements link Trunyan’s temple architecture to an era long before Indian religious influence reached Bali.

At the heart of the temple stands a remarkable six-meter-high statue of Bhatara Da Tonta, meaning “the god who is the center of the world.” The temple itself takes its name from this deity, who is also known as Ratu Gede, or “the Great Lord.”

This statue, made of stone and clay, is thought to be either a pre-Hindu relic or a later adaptation of a much older figure. Its form resembles ancestral depictions from East Nusa Tenggara rather than the familiar Balinese iconography. Depicted nude, it shows a phallus extending downward, with a vaginal symbol beneath it—interpreted as a lingga-yoni, symbolizing cosmic and human fertility. Every three years, during a secret ceremony closed to outsiders, the statue is ritually coated with a mixture of chalk, volcanic tuff, and honey, and adorned with gold ornaments.

This ancient figure is believed to embody the male principle (purusa), while the female counterpart (pradana) is represented in the shrine of Ida Ratu Ayu Dalem Pingit, a three-tiered meru. Together, these elements express the fertility beliefs of the Trunyan community. The statue is thus considered deeply sacred, and it is usually not shown to outsiders. In the 1950s, the Dutch archaeologist J.C. Krijgsman, former Head of the Archaeological Bureau in Gianyar, Bali, was comissioned to renovate it structurally, after completing some respectful renovation work on Pura Puncak Penulisan, a temple of particular importance to Bali Aga/Bali Mula communities.

The cult of Ratu Gede Pancering Jagat is closely tied to the sacred Barong Brutuk dance, performed every two years during the full moon of Kapat (around October). This ritual marks the descent of the divine manifestations Ratu Gede Pancering Jagat, Ratu Ayu Dalem Pingit, and Ratu Sakti Maduwegama.

In 2007, the temple suffered severe damage when a large tree fell, destroying 17 shrines, three candi bentar (split gates), and the surrounding wall. Restoration efforts were later carried out through community cooperation.

A Closed Community

Trunyan’s independence is legendary. One of Bali’s earliest written documents—a royal edict from 911 CE—granted the village exemption from certain royal taxes, perhaps after failed attempts at subjugation. The people of Trunyan have long been known across Bali for their proud and somewhat forbidding character, which is often mistaken for unfriendliness by occasional visitors.

Equally famous, or infamous, is their burial tradition. Unlike the rest of Bali, cremation is not practiced here. The dead are placed in bamboo cages at a sacred site on the lakeshore, accessible only by boat, and left to decompose naturally. A fragrant tree known as taru menyan (“the tree that smells sweet”), after which the village of Trunyan is named, is said to neutralize the odor of decay. In this way, the deceased are gently returned to nature — a transition from one stage of existence to another, reflecting the deep continuity between life and death in Bali Aga/Bali Mula cosmology.

Bibliography

Exelby, Narina and Eveleigh, Mark Verborgenes Bali. Berlin: Jonglez Verlag, 2024.

Goris, Roelof and Dronkers, Pieter Leendert Bali: Atlas Kebudajaan; Cults and Customs; Cultuurgeschiedenis in Beeld. Jakarta: Pemerintah Republik Indonesia, 1950.

Haer, Debbie Guthrie, Morillot, Julliet and Toh, Irene Bali, a Traveller’s Companion. Singapore: Didier Millet, 2007

Hobart, Angela and Ramseyer, Urs and Leemann, Albert The Peoples of Bali. Oxford and Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers, 1996.

Kempers, A. J. Bernet Monumental Bali. Singapore: Periplus Editions, 1991.

Spitzing, Günter Bali. Tempel, Mythen und Volkskunst auf der tropischen Insel zwischen Indischem und Pazifischem Ozean. Köln: DuMont, 1983.

Previous temple:

Next:

Text and photos © Alida Szabo